Dia de Los Muertos Festival: Remembering and Celebrating the Dead

I recently realized that in nine years of living in LA, a city where 32% of the population identifies as Mexican-American, I have never attended a Dia de Los Muertos Festival.

This year I set about changing that enormous oversight.

Disclaimer: Lose the Map contains affiliate links and is a member of Amazon Services LLC Associates Program. If you make a purchase through an affiliate link, I receive a small commission at no extra cost to you.

One of the reasons I love living in Los Angeles is that it is a microcosm of so many cultures around the world. It’s a wonderful place to get exposed to foods and traditions beyond the ones you know.

However, when you experience other cultures, it isn’t just about trying different food and observing different customs. It’s about having your viewpoints and preconceptions challenged.

And for most people, observing the Day of the Dead challenges one major assumption most of us have – how we should view and think of death while we are still alive.

So what is Dia de Los Muertos – the Day of the Dead – about? And what is this Mexican holiday like in Los Angeles? I headed down to historic Olvera Street to find out.

Day of the Dead Facts

The Day of the Dead is Not Mexican Halloween

The Day of the Dead is celebrated over 2 days – November 1 and November 2. The souls of the children are thought to return on the first day, and the departed adults join them on the second day. Some say it technically starts the eve of October 31, when children make a children’s altar for the celebration.

Though it was created by Aztecs and Toltecs, when the indigenous people of Mexico were converted to Catholicism, it eventually fused with the Christian calendar; thus, it is now celebrated on All Saints’ Day and All Souls’ Day.

In other words, Dia de Los Muertos is NOT Mexican Halloween (and please stop calling it that).

It Was Not Initially a Mexican Celebration

Since Dia de Los Muertos has its roots in Aztec and Toltec culture, it was originally celebrated only in central and southern Mexico.

Different indigenous groups lived in the northern parts of the country, so their descendants didn’t share this tradition.

However, the Mexican government instituted Dia de Los Muertos as a national holiday in the 1960s. The state wanted to implement a celebration of indigenous traditions.

Today, the holiday is also observed in plenty of other countries, like Guatemala and Bolivia.

Dia de Los Muertos is Not a Day of Sorrow

This, to me, was the most important realization.

For many of us accustomed to other traditions, we might naturally expect a “Day of the Dead” to have an air of sadness. After all, many of us, including myself, were taught that to laugh, sing, or dance on a day of mourning is disrespectful to those who have died.

Nothing could be further from the truth on Día de Los Muertos.

Mexicans who observe the Day of the Dead see it as a celebration of the lives of dead family and friends. The tradition teaches that during the celebration, our deceased loved ones return to earth and happily join the living.

The Aztecs thought that mourning the dead was disrespectful. They saw death as a natural and welcome part of life, and the departed as members of the community to be cherished.

As a result, plenty of music, dancing, and color is used to mark Day of the Dead festivities.

Day of the Dead Traditions

Ofrendas (Offerings)

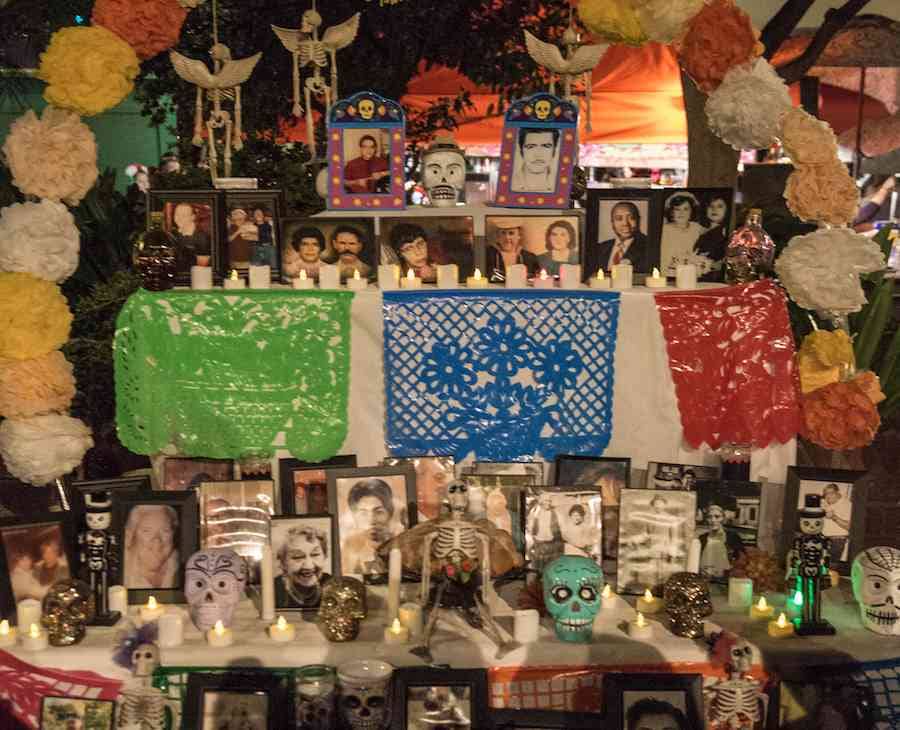

To observe Dia de Los Muertos, families build traditional ofrendas (offerings) – altars with photos of the deceased they wish to honor. These altars have photos of the departed, as well as their favorite food and drinks, and perhaps some trinkets.

The idea is that living and deceased family members can sit and share a meal.

Olvera Street, where I saw the Day of the Dead, is a historic quarter that includes a Mexican marketplace. Many of the shopkeepers now descend from the same vendors who ran those stores 100 years ago.

Therefore, on Olvera Street, you will pass an ofrenda with photos of all the previous shopkeepers that worked there – a nice remembrance of those who left their mark on this area.

Skull Face Painting

There are arts involved in the Day of the Dead as well! People attending the Dia de Los Muertos celebration often get their faces painted into skulls.

Revelers frequently get their skulls drawn with a smile. After all, the idea of the event is not to mourn, but to embrace death and remove the fear of it.

If the drawing process seems too complicated (coming from someone who hasn’t mastered eyeshadow yet, it is), the celebration in Olvera Street has a station where artists will draw the skull on you. I imagine most celebrations have something similar.

Pan de Muerto

Pan de Muerto is a sweet bread baked before Day of the Dead celebrations. Relatives will leave it on ofrendas for their dead loved ones.

People will often bake and give out pan de muerto to those attending the Dia de Los Muertos festival.

Day of the Dead Decorations

Calaveras

Yes, there are skulls everywhere. Not unexpected in a Day of the Dead kind of setting.

Calaveras are basically sugar skulls; people often leave them on ofrendas. I imagine if eaten, the ensuing rapid insulin spike gets you one step closer to empathizing with the dead.

The best known Calavera is probably Dia de Los Muertos’ Catrina. Around 1910, political cartoonist Jose Guadalupe Posada drew a rich dead Mexican woman in fancy French dress to mock the Europeanization of the Mexican upper class at the time.

She eventually became the figure of Catrina (a slang term for “rich”), and many Mexicans draw her or dress up as her for Dia de Los Muertos.

Marigolds – Flor de Muerto

Cheerful-looking marigolds are the unofficial Day of the Dead flowers. Family members of the deceased create pathways using the marigolds that lead the dead to the ofrendas.

Why choose marigolds? Their bright yellow colors and subtle scent supposedly attract the dead. According to tradition, lovely marigolds are a symbol of the beauty and fragility of life.

Final Thoughts on Day of the Dead

In order to share my thoughts about Day of the Dead, I think I first need to share a personal story. Well maybe not “need”, but it’s my blog, so I’ll write what I want.

Experiences With Mourning

I remember my grandfather’s funeral when I was 16. It was a difficult day. I had been very close to him, as we would live in the same house for half the year.

I was sitting with my cousins in the living room after the funeral and they were trying to cheer me up. Nostalgic with memories of happy times we had shared with my grandfather, we remembered a song we had made up when we were young. We would sing it to our parents and grandparents in the morning when we were all under one roof for a major holiday.

We started singing and laughing at the memory of us being young and tone-deaf and stupid. Still, I remembered how adorable my grandfather thought we were when we sang it.

Suddenly, one of the adults walked in and loudly shushed us. “We had a funeral today! You can’t sing”. To clarify, he meant it in a “you shouldn’t sing” kind of way, rather than “you can’t sing”, a fact which we already knew.

We quieted down and I felt my sadness wash over me again.

One Way to Remember the Dead?

I remember, even then, how unfair and ridiculous that felt. I remember thinking that my grandfather would probably have loved to see us going over these memories we had with him. He would be happy to see my cousins and I supporting each other and cheering each other up, indulging in this beautiful nostalgia of him.

Why should there only be one acceptable way to mourn? And why can nothing happy intrude on it?

While I was standing in the crowd at Olvera Street, the leader of the Dia de Los Muertos festival spoke in Spanish about the significance of the day. The paraphrased (I was trying to type my notes as fast as possible) speech that moved me was this:

“Life is fleeting and death is our companion from the day we are born. We need to accept it and embrace it. Today, we give a name to this thing (death) that is sacred. Sacred because all of us are just passing through.”

In other words, let’s accept and celebrate the natural outcome of our life, of all our lives. We celebrate the dead and remember them because inevitably, we will all join them.

I thought, how wonderful to have this healthy outlook on life, and on the scariest part of life for most people: death. How beautiful to embrace the inevitabilities we cannot change, and how lovely to be able to laugh and sing and share a meal with our loved ones who are no longer physically with us but are in our hearts.

Todos Somos Calaveras

There is a saying in Spanish, especially popular around the time of Dia de Los Muertos: “todos somos calaveras” – we are all skeletons.

You can choose to view this as a dark kind of thought. Or you can choose to view it as a freeing embrace of life.

As one woman at the head of the procession said to the crowd: “In the spot where I am standing, I am the most important person. But in the universe, I am nothing”.

I encourage anyone living in LA, or anywhere in the United States or abroad where you can observe a Day of the Dead celebration, to do so.

I personally went to Olvera Street, but there is also an enormous celebration in the Hollywood Forever Cemetery in LA – arrive before 4 PM otherwise you can expect to spend most of your time on line.

If there’s no celebration near you, try to plan a trip to Mexico during the Day of the Dead – you won’t regret it!

Have you been to a Day of the Dead celebration? What did you think?

If you want to share or save this post, Pin away!

Love the post! I can definitely feel the amount of thought that went into this and appreciate your explanation of this wonderful event.

Thank you so much! This is honestly the best feedback I can get, I always try to represent events like this accurately and with appreciation :)