Life in Idomeni: 9 Realizations in a Refugee Camp

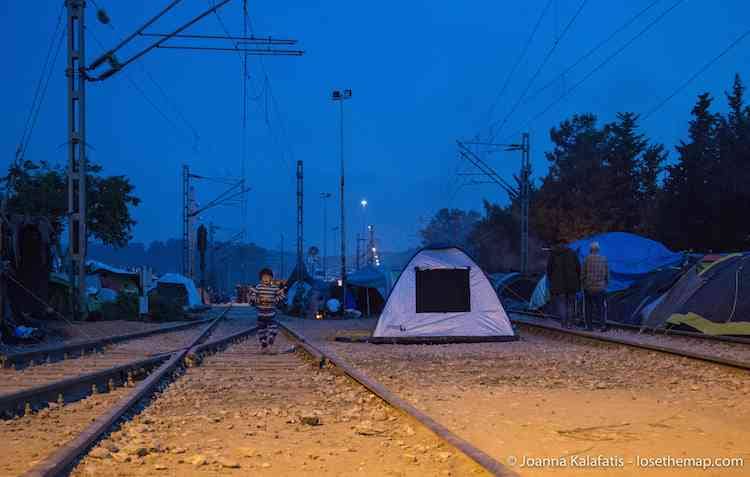

Everything in Idomeni refugee camp was a contradiction. Plastic fumes suffocated the air while children wildly laughed. Families, or what remained of them, would chat animatedly with their neighbors and warmly offer passerbys food; then once in a while the restlessness and frustration of being stuck in place, of any possible future slipping away day by day, would boil over, and confrontations would escalate into shouting matches.

Fiercely competitive soccer matches took place in front of a Doctors Without Borders tent. Occasionally someone would be rushed in from one of the thousand ailments one can contract when sleeping in tents and eating small portions of sunbaked food for weeks on end, trying in vain to keep out rats on rainy days. With each new patient, the pause in the match would only be seconds long.

Disclaimer: Lose the Map contains affiliate links and is a member of Amazon Services LLC Associates Program. If you make a purchase through an affiliate link, I receive a small commission at no extra cost to you.

I spent a lot of time every day talking to my new friend, Omar. I would include his picture here, but he was terrified of having to go back to Syria and potentially being identified through any online photos as a refugee by ISIS. He would be killed.

Omar’s smile was always so easy, so charming and so bright that it took me three days to see his limp. Then one day he wore shorts and I could see the missing parts of his leg that had been removed by a bomb. Back in Syria.

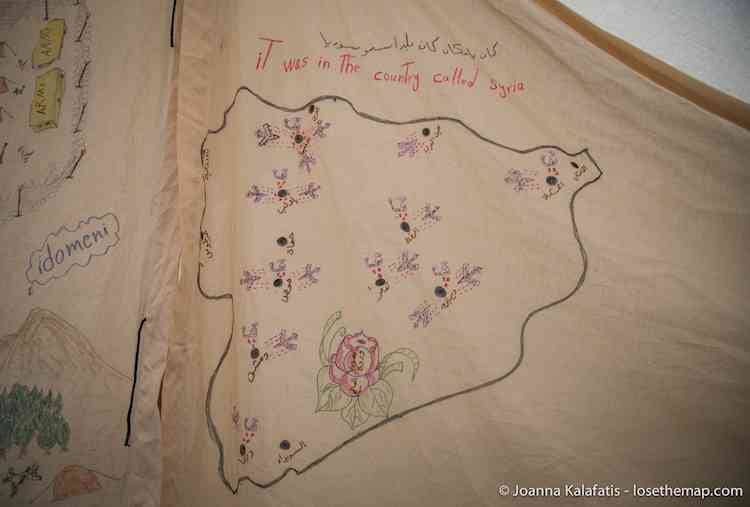

That’s one thing I heard a lot in the camp: Syria. But it was never a simple word. It was a wistful exhalation, usually repeated, as though the speaker thought he could conjure up the ghost of his home with a chant: Syria..Syria….Syria.

Unlike Dorothy in Oz, words and wishes couldn’t bring back the wrecked homeland the refugees carried with them, the dearly-held images of their houses and neighborhoods, children, parents, favorite aunts, crushes, childhood friends, the kind old woman two houses over, the shop owner they would pass every morning – all deceased, now etched only in their minds.

Before I continue: this obviously won’t be my usual light and breezy article with some facts and humor thrown in for good measure. Idomeni has now been torn down and the refugees displaced, just days after I left the refugee camp. Some of the post will focus on how the refugee camp affected me and changed some of my thinking. I struggled with this because it seemed so selfish when so many are suffering to somehow bring the focus back to what I felt; but I can only write what I know and what I experienced.

I can only show you Idomeni refugee camp as I saw it through my eyes.

So what did I see?

First Impressions Are Disturbingly Normal

I don’t know what I expected upon entering the refugee camp. To see bowed, huddled masses? Some stupid, generic image of sad, downtrodden people had ridiculously and unintentionally formed in my head before my first day there.

The first time I walked in, two teenage girls with surprisingly well-applied makeup for their age, sharing headphones, giggled and chatted as they passed by me. Further in, a boy no older than 9 was wildly gesticulating and clearly unhappy with the call his opponent had just made in an informal soccer game. Men gathered around tents and benches of the refugee camp, with that air middle-aged men gathered together in groups always have – bent poses and thoughtful expressions suggesting they are discussing issues of meaningful, revolutionary importance, and cannot be disturbed.

A blushing on-the-verge-of-being-a-couple in their 20s strolled by together and cast side glances at each other, unable to contain their smiles when looking back at the ground. A short, tired-looking woman in her 30s tried in vain to contain the boundless energy of her two toddlers so that they might, at some point, sit down.

This could have been any town square anywhere. It was disconcerting to see it here.

Until You Take a Second Look

So on the surface, everything in the refugee camp looked perfectly normal, which was somewhat abnormal for the horrendous situation in which the refugees found themselves.

And then I remembered something I had read about grief – that in times of distress, people try their best to keep up their routine. After sitting down with many refugees and having actual conversations, it was clear this was the case here as well.

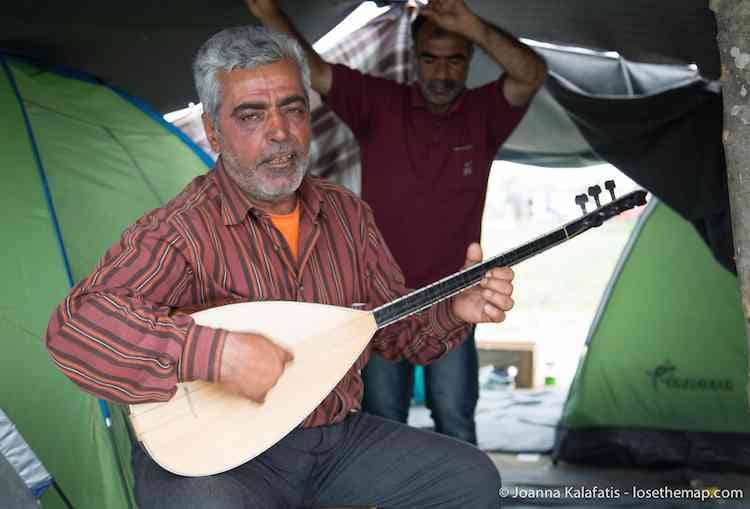

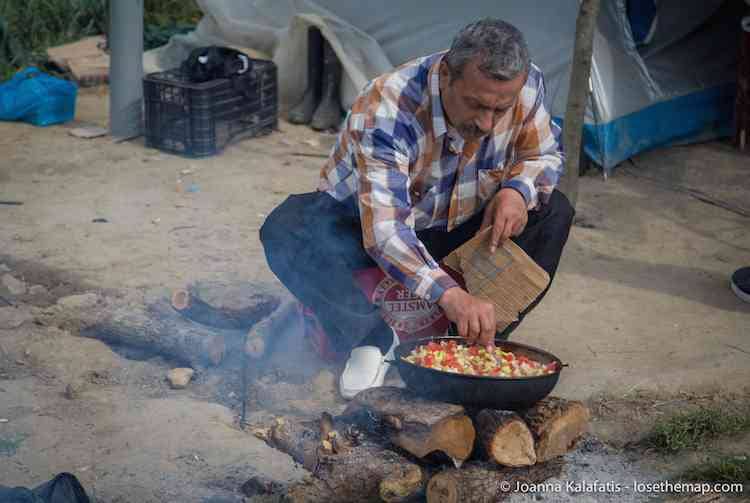

People were trying to keep up their habits, their hobbies, their appearance, the rhythms of their home as much as possible. The reasons were all along the same lines: so they could keep busy, so that they could avoid distressing their kids; so they could keep a shaky hold on their normalcy, their sanity, their life. So they could avoid thinking about the fact that they were stuck in a refugee camp, feeling useless, feeling unoccupied, with little hope of going forward, and barred from going back. These thoughts inevitably crept in during our talks.

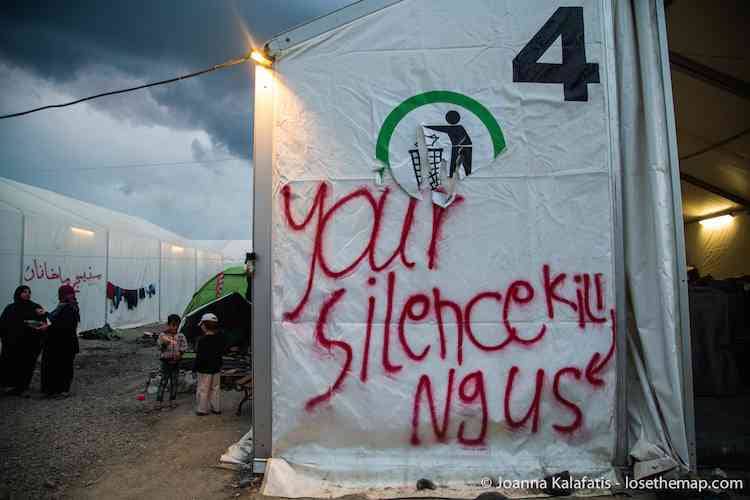

Grown men and proud fathers broke down crying when they spoke about their homes back in Syria. In the span of one conversation, people switched from hopeful questions about the border reopening to confessions of depression, suicidal thoughts, of giving up hope and wanting to go back to their country and die.

“If I knew they’d close the borders I wouldn’t have left. I’d rather risk a quick death in Syria than live out a slow death here”.

Once heard, that’s not a sentiment I can forget.

The Generosity is Overwhelming

People would not let us leave their tents unless we had accepted their meal, their Coca-Cola, their cigarette, their tea. My Greek grandmothers would have been proud of the insistence with which these relative strangers in the refugee camp forced food down my throat.

Each time, I would only take the tiniest of bites, obviously feeling guilty about having to take any part of the little food they had. But they wouldn’t take no for an answer.

I don’t know if it’s a product of their culture, religion, or simply their situation at the moment, but the hospitality and generosity I experienced from my refugee friends was overwhelming.

One of the First Camp Casualties is Pride

Pride was the first to go in the camp. Pride in its positive sense, in the sense of being a productive member of society, providing for your family, holding a respectable position.

Tahar, with his son and daughter shyly huddled up to him, showed us pictures of his rather large and impressive home in Syria. (Some people have a misconception that the refugees came from dire poverty. Syria was in fact quite progressive and relatively well off economically, so this is not at all the case.) He spoke to us about his work, how he had taken care of his wife and children with the money he made and saved enough to be able to educate his kids.

Now his wife is dead and his family’s food and shelter is at the whim of governments and volunteers.

“I feel like a stray dog, waiting for them to give me food so perhaps I can feed my children”.

Muhammad chimed in next to him: “I don’t want people to give me things. I worked in Syria, I can work here again. I just need them to let me work.”

People hated feeling useless most of all. Those who could get their hands on products like SIM cards and cigarettes, or make some food, set up small shops and got a local economy going. It was the only way to cope and perhaps raise some funds.

The Children Are Incredible

I am not a kid person. My parents, best friends, ex-boyfriends, and literally anyone else you ask can attest to that. Maybe occasionally when a baby is pushed by I’ll join in the general “aw-ing” for a second, just enough to assure people that I am not a heartless black hole devoid of the maternal instinct, and that’s usually the end of it.

But the children in Idomeni broke me.

After the first day we met, Ahrin and Oly followed me everywhere. They would locate me within minutes of entering the camp, each grab a hand, and walk with me wherever I went. Then we would play some version of Patty Cakes that I lost several times.

The smallest things could make them and their friends happy. We spent an hour laughing over Snapchat filters. It was cathartic and beautiful in the middle of so much discarded hope.

You Can Never Help As Much As You Want in a Refugee Camp

I met some wonderfully dedicated volunteers in Idomeni. They helped provide food, medical care, wash the children, and perhaps most importantly, spent time listening to and caring for people who needed an outlet for their pain. One of the best volunteer efforts I saw was the local cultural center, where some volunteers from Spain held dances and singing events with pop hits from Syria.

So yes, in some ways, we could all help.

But I couldn’t do the big things my refugee friends really wanted. I couldn’t open the border. I couldn’t reunite families that had been torn apart between Germany and Idomeni camp, or make Syria safe again. I felt powerless and terrible.

I couldn’t even do some smaller things. We met a very pregnant woman who had been returned by the FYROM police after an attempt at crossing the border. It was an 11 km walk to the camp, and she asked us if she could fit in our car. She could. But the police had given strict orders not to transport any refugees, or we would be considered smugglers. So we had to say no.

The Worst Part is Leaving Everyone Behind

I thought I would break down crying at some point in the refugee camp. I never did. Even if the urge arose somewhat rarely, it felt almost offensive to sit there crying in front of people who had lost so much, as though I could ever truly understand or empathize. Being in the camp every day didn’t bring me down as I thought it would.

Leaving did.

The day before we left, a huge confrontation between police and refugees broke out in Idomeni. The entire camp was tear gassed, and as my throat burned I wrapped a sweater around my face to stop the pain lighting up in my eyes. I had brought gifts for the kids – some mermaid dolls and a soccer ball. In the midst of all the confusion, with the refugees pouring out of the camp to try to get some fresh air, I remember feeling strangled by the thought that I would never see the kids again and they wouldn’t get their presents. That I might have to leave without having them hug and kiss me one last time. I had told them I would be there with gifts that day, and I was forced to break my promise.

I eventually got the presents to Ahrin, but I didn’t see Oly again. I found Omar and his friends at the last second before having to hit the road and catch my plane, as they had abandoned their usual post and moved to another part of camp.

Leaving behind Ahrin, Oly, Omar, Mahmoud, Tahar, Maroua, all the people that had shared their stories and opened up their temporary homes to me – that was the worst part. I’ve kept WhatsApp numbers and kept in touch with some, but knowing that their future is up for grabs and there is not much I can do, while I go back to my comfortable, peaceful home surrounded by friends and family, is heart wrenching to a degree I couldn’t imagine.

‘Home’ Is More Important Than We Think

This is one I wanted to put out there specifically for my fellow travelers and travel bloggers. We tend to scorn the concept of “home” sometimes. “My home is the world”, I sometimes hear. My nomadic friends travel all over without usually looking back, and insist they would never go back to what they left.

I love to travel myself, and I don’t mean to say anything negative about this lifestyle – I think it takes an especially brave person to leave behind familiar comforts and wander the world.

But in my days in Idomeni refugee camp, I saw that this luxury of being able to abandon “home” without a care is a privilege. Refugees were torn away by violent circumstance, not by choice. More importantly, for many of them, there is no home to which they can return. Their neighborhoods don’t exist and half the people they knew aren’t there anymore because they have been displaced or killed.

“Home” is not a concept to be taken lightly. Having the choice to go back and once again see people there who love us is not a privilege we all have. It’s a beautiful thing to have a place in this world where you can speak your language with others, share the same culture, the same lifestyle, and the same history. This is what had been torn away in Idomeni, and perhaps it shouldn’t be disregarded so casually by the rest of us.

In the Worst of Circumstances, There Are Still So Many Beautiful Moments

I don’t want to leave you all with the most depressing moments from my time in the camp. Even in the worst of circumstances, I believe people still have a tremendous capacity for finding joy and beauty, and I saw it every day in Idomeni.

Photos can take over where words fail, so I’ll leave you on a positive note with these:

Please help the Syrian refugees in this refugee camp and many others by donating to Hope for Syria.

This was an incredibly powerful read. Thank you so much for sharing.

Thank you very much Brianna! Glad it moved you :)